Introduction to unix

Table of Contents

Unix File System

In Unix, everything is represented as either a file or a process. Files represent passive data, such as streams of bytes stored on disk, while processes are active entities that read, modify, and write this data. A file cannot act on its own — it requires a process to interact with it.

The Unix File System is structured as a single, inverted tree. At the top of this hierarchy is the root directory (/), from which all other directories and files branch out. Directories are themselves special files that can contain other files, including subdirectories, forming the hierarchical tree structure.

One of the defining features of Unix is that it maintains the illusion of a single, unified file system. In reality, the file system may span multiple partitions, physical disks, or even remote machines over a network. However, to the user, these components appear seamlessly integrated into the same directory tree. This abstraction hides the complexity of physical storage and provides a consistent view of the system.

Within this structure, everything — user files, programs, and even hardware devices — is represented as part of the same namespace. By convention, system programs, device files, and user home directories are organized into their respective subdirectories, ensuring clarity and separation of responsibilities while preserving the unified tree model.

On a Unix system, each physical disk is usually divided into several "slices" or "virtual disks", with each containing its own hierarchical file system. To present a single, unified filesystem to the user, these individual filesystems are combined. Among them, one filesystem is designated as the root filesystem. Additional filesystems are integrated into this hierarchy through a process called mounting. When mounted, a filesystem is attached to a specific directory known as a mount point. From that point onward, any access to the directory transparently crosses into the mounted filesystem, allowing the kernel to retrieve files seamlessly. Moreover, filesystems can also be mounted on directories within other mounted filesystems, forming a tree-like structure of nested filesystems.

Shell

When a Unix system starts, the very first process launched is init. This process is responsible for preparing the system for use, creating essential child processes that configure the environment, and eventually presenting a login prompt to the user.

After a successful login, init spawns a new child process known as the shell. The shell is an interactive program that provides a command-line interface, allowing users to execute commands. Each command entered by the user typically results in the shell creating a new child process to perform the requested task, making the shell the parent of those processes. In turn, the shell itself remains a child of init.

This parent-child relationship gives rise to a process tree, rooted at init (the ancestor of all processes). From init, the shell emerges, and from the shell, additional processes are spawned, forming multiple generations of processes that branch out dynamically as the system is used.

The login process ensures that each user is properly identified and associated with the correct resources. When logging in, the system verifies the user's identity (via username and password) and assigns them a UID (User Identifier) and GID(Group Identifier). These numeric identifiers are used internally by the system to manage permissions and ownership of files and processes. Once authenticated, the user is placed in their home directory and provided with an initial shell to begin interacting with the system.

What is the inode?

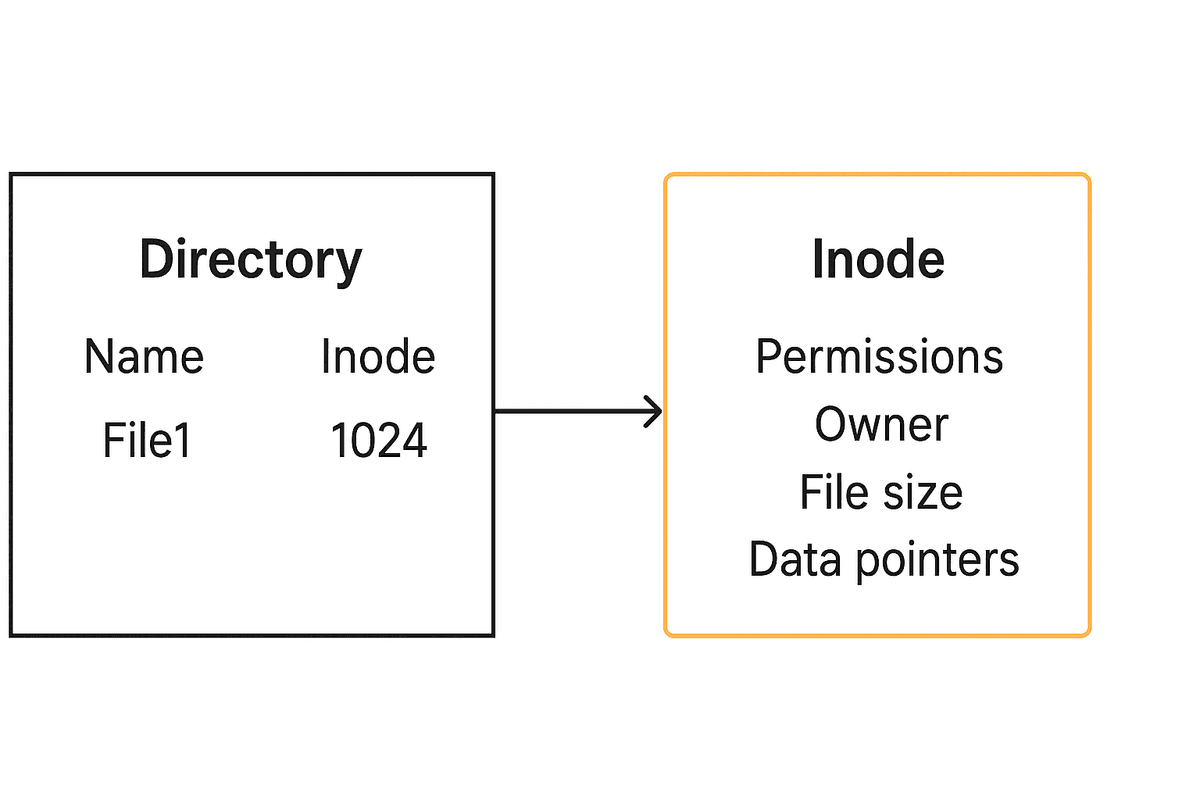

An inode (index node) is a fundamental data structure in Unix-like file systems. It stores metadata about a file but does not contain the file name or actual data. Each file has a unique inode number, which the operating system uses to locate and manage the file.

Information typically stored in an inode includes file permissions and type (such as regular file, directory, or symbolic link), ownership details like UID and GID, file size, and various timestamps including creation, modification, and last access time.

Inodes also keep track of the link count, which represents the number of directory entries pointing to the file. This allows multiple filenames to reference the same underlying data without duplication.

Another important role of the inode is to maintain pointers to the actual file contents stored on disk. Depending on the file system implementation, these may include direct, indirect, double-indirect, and triple-indirect pointers to handle both small and very large files efficiently.

One key point is that file names are stored in directory structures, not inside the inode itself. This separation makes it possible for multiple filenames (hard links) to point to the same inode, enhancing flexibility in file management.

Hard Links

In Unix, hard links provide the ability to make a file appear as though it exists in multiple locations. A hard link is simply another name (directory entry) pointing to the same inode. Since both names share the same inode number, they ultimately reference the same file contents on disk.

A file must always have at least one link (its filename), but it can have multiple links as needed. Removing a filename with the rm command decreases the link count of the inode. When the link count drops to zero, the inode and its data blocks are released, effectively deleting the file. Internally, this is handled by the unlink() system call.

1ln f1 f2By default, ln creates hard links. However, hard links cannot span across different file systems or partitions. In such cases, the -s option is used to create a symbolic link instead.

Directories also rely on links to maintain the hierarchical structure of the file system. Every directory has at least two special hard links: . (a link to itself) and .. (a link to its parent). These links are automatically created when a new directory is made. To preserve the integrity of the filesystem and avoid infinite loops, only the mkdir command can create hard links to directories. For other cases where directory linking is needed, symbolic links are used instead.

Symbolic Links

A symbolic link is a special type of file whose content is simply the pathname of another file. Unlike a hard link, which points directly to an existing i-node, a symbolic link points to a new i-node that stores a reference to the target's path.

When you access a symbolic link, the filesystem automatically resolves the stored pathname and redirects the I/O operations to the referenced file. This indirection means symlinks can cross filesystem boundaries and even point to non-existent files (often called dangling links).

One key difference from hard links is what happens when the target file is deleted:

• If the file is removed, the symbolic link becomes invalid because the pathname it holds no longer resolves to a valid file.

• In contrast, if it were a hard link, deleting the original file would only decrement the link count on the i-node, and the other links would still function correctly.

To create a symbolic link named new that points to file, use:

1ln -s file newInput and Output Redirection

In Unix, every command interacts with three standard file streams: STDIN (standard input, file descriptor 0), STDOUT (standard output, file descriptor 1), and STDERR (standard error, file descriptor 2). By default, STDIN comes from the keyboard, while STDOUT and STDERR are displayed on the terminal. Using redirection operators, the shell can change where input is read from and where output is written.

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

> file | Redirect STDOUT to a file (overwrite if file exists). This opens a writing end to the file. | ls > out.txt |

>> file | Append STDOUT to a file (preserve existing content). | echo "hi" >> log.txt |

< file | Redirect STDIN from a file instead of the keyboard. This opens a reading end from the file. | sort < names.txt |

2> file | Redirect STDERR to a file (overwrite if file exists). | grep foo * 2> errors.log |

2>&1 | Redirect STDERR to the same place as STDOUT. | cmd > out.txt 2>&1 |

| (pipe) | Send STDOUT of one command as STDIN to another. | cat file | grep "word" |

These redirection operators are handled by the shell before the command is executed. This allows processes to remain unaware of where their input is coming from or where their output is going, making Unix tools highly flexible and composable.

Permission Bits for Files and Directories

In Unix-like systems, every file and directory has permission bits that control access. These bits determine whether a user can read, write, or execute a file (or list, create, and search a directory). The ls -l command displays these permissions along with additional metadata such as the number of links, owner, group, size, and modification time.

| Symbol | For Files | For Directories |

|---|---|---|

r | Read file contents | List directory contents |

w | Modify or delete file contents | Create or delete files in directory |

x | Execute file as a program/script | Access directory and traverse its path (needed for cd) |

s (setuid/setgid) | Run file with owner's or group's privileges | - |

t (sticky bit) | - | Only file owners (not others) can delete their files in this directory |

1simzhefengkenneth@sims-MacBook-Air github % ls -l

2total 0

3drwxr-xr-x@ 11 simzhefengkenneth staff 352 Aug 1 19:51 BlockChain

4drwxr-xr-x@ 13 simzhefengkenneth staff 416 Aug 17 20:53 CppConcurrencyPractice

5drwxr-xr-x@ 7 simzhefengkenneth staff 224 Aug 7 09:07 CppOrderbookThe permission string (e.g., drwxr-xr-x) is broken down as: the file type (d for directory, - for regular file,l for symbolic link), followed by three sets of rwx bits for owner, group, and others. The number following it shows the link count (e.g., 11), then the owner (simzhefengkenneth), the group (staff), the size in bytes, last modification date, and finally the file or directory name.

SetUID and SetGID

Normally, when a user runs a command, the new process inherits the user ID (UID) and group ID (GID) from the parent shell. This means that all actions taken by the process are performed with the user's own permissions. However, some system tasks require elevated privileges that a normal user does not have. For example, updating a password requires modifying the /etc/passwd or /etc/shadow file, which only root can write to.

To solve this, Unix systems provide the SetUID and SetGID permission bits:

| Bit | Effect | Example |

|---|---|---|

SetUID (s) | Process runs with the file owner's UID instead of the user's UID. | -rwsr-xr-x 1 root root /usr/bin/passwd |

SetGID (s) | Process runs with the file group's GID instead of the user's GID. For directories, new files inherit the directory's group. | drwxr-sr-x 2 user staff shared_dir |

For example, the passwd program is owned by root and has the SetUID bit set. Even if a normal user runs it, the process runs with root's UID, allowing it to safely update the system password database:

1$ ls -l /usr/bin/passwd

2-rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 54256 Aug 1 12:34 /usr/bin/passwd

3

4$ id

5uid=1001(alice) gid=1001(alice) groups=1001(alice)

6

7$ passwd

8Changing password for alice.

9New password: ****Without the SetUID bit, the passwd program would inherit the user's UID and would not be able to write to /etc/shadow. Similarly, the SetGID bit is often used for collaborative project directories where all files should share the same group ownership.

Sticky Bit

Directories like /tmp are often writable by all users so that any process can store temporary files. However, if a directory is writable by everyone, then without additional protection, users could remove or rename files that they do not own, simply because they have write access to the directory itself.

For example, suppose user alice creates a file in /tmp:

1# As alice

2$ echo "secret" > /tmp/alice_file.txt

3$ ls -l /tmp/alice_file.txt

4-rw-r--r-- 1 alice users 7 Aug 17 12:00 /tmp/alice_file.txtNotice that only alice has write permission to the file. However, because /tmp itself is world-writable:

1$ ls -ld /tmp

2drwxrwxrwx 10 root root 4096 Aug 17 12:00 /tmp

3

4# As bob (another user without write permission to alice_file.txt)

5$ rm /tmp/alice_file.txt # succeeds if sticky bit is not set!This is dangerous because it allows one user to delete or rename files belonging to another. To prevent this, the sticky bit(represented as t in the permission string) is applied to shared directories like /tmp.

1# Enable the sticky bit on /tmp

2$ chmod +t /tmp

3$ ls -ld /tmp

4drwxrwxrwt 10 root root 4096 Aug 17 12:00 /tmp

5

6# Now if bob tries again:

7$ rm /tmp/alice_file.txt

8rm: cannot remove '/tmp/alice_file.txt': Operation not permittedWith the sticky bit set (t at the end of the permission string), only the file owner, the directory owner, or root can remove or rename a file. This ensures shared directories remain usable while protecting individual users' files from being tampered with, even if the directory itself has full write permissions.

umask

The umask defines the default permission bits that are removed when new files and directories are created. In other words, it specifies which permissions should not be set by default.

By default, directories start with a maximum of 777 (read, write, and execute for everyone), and files start with 666 (read and write for everyone). The umask subtracts bits from these maximums.

For example, a common umask value is 022. This removes write permission for the group and others:

777 - 022 = 755 (rwxr-xr-x)666 - 022 = 644 (rw-r--r--)Notice that files never get the execute bit (x) by default, since most files are not programs. If execution is needed, it must be explicitly added using chmod.