Introduction to Rust

Table of Contents

Why Rust?

1void example() {

2 vector<string> vector;

3 ...

4 auto& elem = vector[0];

5 vector.push_back(some_string);

6 cout << elem;

7}In this example, pushing a new element into the vector may cause it to resize and reallocate its memory. If that happens, all existing references— including elem—will point to invalid memory. This leads to undefined behavior, as elem becomes a dangling reference.

The root cause of this issue is the allowance of aliasing—multiple references or pointers to the same memory. Here, elem refers to the original location of vector[0], while the vector itself is being modified and possibly relocated.

When one of the aliased references changes the underlying data or its location, the others may be left pointing to freed or invalid memory. This is a core safety problem in C++ and other systems languages that allow unrestricted aliasing. Rust prevents these kinds of bugs by enforcing strict ownership and borrowing rules at compile time.

Ownership in Rust

1fn main() {

2 let mut book = Vec::new();

3 book.push(...);

4 book.push(...);

5 publish(book);

6 // a second call to publish would

7 // generate a compilation error

8 // publish(book);

9}

10

11fn publish(book: Vec<String>) {

12 ...

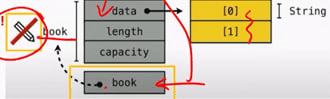

13}In the main function, we create a mutable vector called book and add two elements to it using book.push(...). Initially, main owns the vector because it was created there using let mut. In Rust, variables are immutable by default, so the mut keyword is required to make the vector mutable.

When we call publish(book), ownership of the vector is moved to the publish function. This is not a copy; it's a move—meaning main can no longer use book after this point.

Attempting to call publish(book) a second time will result in a compilation error because main no longer owns book. Rust enforces these ownership rules at compile time to ensure memory safety without needing a garbage collector.

Immutable borrow(Shared reference) in Rust

1fn main() {

2 let mut book = Vec::new();

3 book.push(...);

4 book.push(...);

5 publish(&book);

6 // a second call to publish would

7 // borrow again the reference to book.

8 // compilation is successful

9 publish(&book);

10}

11

12fn publish(book: &Vec<String>) {

13 ...

14}Sometimes, you want to share access to data without transferring ownership. In such cases, Rust allows you to create an immutable borrow, also known as a shared reference. This is done using the & symbol.

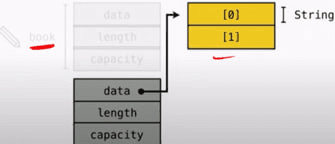

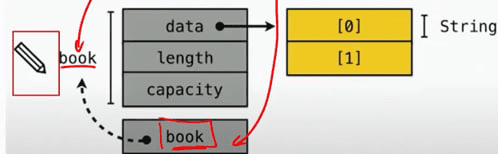

In this example, publish(&book) passes a shared reference of the book vector to the publish function. Because it’s an immutable borrow, publish can read the contents of the vector but cannot modify it.

Shared references do not transfer ownership. The vector book still belongs to the main function, so we can safely call publish(&book) multiple times. Each call temporarily borrows the data and gives read-only access to the function. It is not a shallow copy of the vector, instead it is pointing to our book that we initially created in line 2.

While any shared reference exists, the original data cannot be mutated—neither from main nor from any function holding the shared reference. This rule guarantees data consistency and prevents race conditions at compile time.

You can have multiple shared references active at the same time, but no mutable reference is allowed while shared references exist. This is a key aspect of Rust’s safety guarantees.

Mutable borrow in Rust

1fn main() {

2 let mut book = Vec::new();

3 book.push(...);

4 book.push(...);

5 publish(&mut book);

6 publish(&mut book);

7}

8

9fn publish(book: &mut Vec<String>) {

10 ...

11}In Rust, the &mut keyword creates a mutable borrow. In the example above, the publish function takes a mutable reference to book, which allows the function to modify the original book defined in main.

While a mutable borrow exists, no other borrows—mutable or immutable—can be created. This ensures safe, exclusive access to the data. In this case, while publish(&mut book) is running, main cannot read from or write to book. However, main still retains ownership of book.

After the first call to publish finishes, the mutable borrow goes out of scope. This makes it possible to create another mutable borrow in the second call to publish. Rust allows exactly one mutable borrow at a time. In contrast, you can have multiple immutable borrows as long as there are no active mutable borrows.

This borrowing rule is key to Rust’s safety guarantees—it ensures that data is not accessed concurrently in an unsafe way. Once a mutable borrow ends, the owner (in this case, main) regains full control and can modify the data again or pass it along as needed.

Closures in Rust

In Rust, closures are anonymous functions that can be stored in variables, passed as arguments, or returned from other functions. Unlike regular functions, closures have the ability to capture values from the surrounding environment in which they are defined.

Closures can capture variables in three different ways, which mirror how functions take parameters:immutable borrowing (&T), mutable borrowing (&mut T), and taking ownership (T). Rust automatically infers which of these to use depending on how the closure interacts with the captured variables.

If you want the closure to take ownership of the captured values explicitly—even if it's not strictly necessary—you can prefix it with the move keyword. This is particularly useful when spawning new threads, where ownership of data must be transferred to the new thread.

In the example below, we use move to ensure the list vector is moved into the closure, giving the spawned thread full ownership:

1use std::thread;

2

3fn main() {

4 let list = vec![1, 2, 3];

5 println!("Before defining closure: {list:?}");

6

7 thread::spawn(move || println!("From thread: {list:?}"))

8 .join()

9 .unwrap();

10}Scoped threads in Rust

1fn main() {

2 let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

3 println!("main thread has id {}", thread_id::get());

4

5 std::thread::scope(|scope| {

6 scope.spawn(|inner_scope| {

7 println!("Here's a vector: {:?}", v);

8 println!("Now in thread with id {}", thread_id::get());

9 });

10 }).unwrap();

11

12 println!("Vector v is back: {:?}", v);

13}In Rust, scoped threads ensure that any threads spawned within a scope must complete before the scope itself ends. This prevents common concurrency issues like data races and use-after-free errors, enabling safe access to variables from the parent scope.

In the example above, the vector v is borrowed by the thread created at line 6 using scope.spawn. Unlike regular std::thread::spawn, where data must be moved into the thread (transferring ownership), std::thread::scope allows us to borrow local variables directly.

Since the thread is guaranteed to finish before the scope ends, Rust ensures that v remains valid throughout the thread’s execution. This makes scoped threads ideal for situations where temporary threads need access to local variables without needing to clone or move them.

Scoped threads are useful when you know a spawned thread will not outlive a particular block of code. The Rust standard library provides std::thread::scope specifically to support this pattern, giving you the power to spawn threads that safely borrow non-static data, such as stack-allocated variables.

Rayon

1use rayon; // 1.10.0

2

3use std::sync::atomic::{AtomicI64, Ordering};

4use rayon::prelude::*;

5

6fn init_vector() -> Vec<i64> {

7 vec![5, 10, 7, 20, 13, 100, 1, 200]

8}

9

10fn main() {

11 let vec = init_vector();

12 let max = AtomicI64::new(i64::MIN);

13

14 vec.par_iter().for_each(|n| {

15 loop {

16 let old = max.load(Ordering::SeqCst);

17 if *n <= old {

18 break;

19 }

20 match max.compare_exchange(old, *n, Ordering::SeqCst, Ordering::SeqCst) {

21 Ok(_) => {

22 println!("Swapped {} for {}.", n, old);

23 break;

24 }

25 Err(_) => continue,

26 }

27 }

28 });

29

30 println!("Max value in the array is {}", max.load(Ordering::SeqCst));

31 if max.load(Ordering::SeqCst) == i64::MAX {

32 println!("This is the max value for an i64.");

33 }

34}In this example, we use the Rayon crate to parallelize the process of finding the maximum value in a vector. Instead of iterating through each number sequentially, we utilize Rayon’s par_iter to process elements in parallel.

To handle concurrent updates to the maximum value safely, we use an AtomicI64. Each thread attempts to update this shared atomic variable using compare_exchange, which ensures that only one thread can successfully replace the maximum at a time.

Here's how it works: each thread loads the current value of max and compares it with its own value n. If n is greater, it tries to atomically update max using compare_exchange. This operation will succeed only if no other thread has modified max in the meantime. If it fails, the loop continues until the thread either succeeds or determines its value is no longer the highest.

This approach is both thread-safe and efficient, leveraging Rayon's parallelism and Rust's atomic operations to maximize performance while ensuring correctness.

Arc

When multiple threads need shared ownership of data, Arc (Atomically Reference Counted) is the go-to solution. It allows multiple ownership by keeping a reference count of how many Arc pointers exist to a value stored on the heap. When the last Arc goes out of scope, the data is automatically deallocated.

However, Arc<T> only provides immutable access to T. To enable mutable access across threads, you need to wrap T with a synchronization primitive like Mutex<T> or RwLock<T>.

1use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

2

3fn main() {

4 let my_number = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

5 let mut handle_vec = vec![]; // JoinHandles will go in here

6

7 for _ in 0..2 { // do this twice

8 let my_number_clone = Arc::clone(&my_number); // Make the clone before starting the thread

9 let handle = std::thread::spawn(move || { // Put the clone in

10 for _ in 0..10 {

11 *my_number_clone.lock().unwrap() += 1;

12 }

13 });

14 handle_vec.push(handle); // save the handle so we can call join on it outside of the loop

15 // If we don't push it in the vec, it will just die here

16 }

17

18 handle_vec.into_iter().for_each(|handle| handle.join().unwrap()); // call join on all handles

19 println!("{:?}", my_number);

20}In this example, we demonstrate how to share mutable state across multiple threads using Arc and Mutex. Since threads in Rust require ownership of the values they use, we use Arc to allow multiple threads to own the same value, and Mutex to ensure that only one thread can mutate the value at a time.

The move keyword is necessary when spawning threads, as it transfers ownership of the Arc clone into the thread. Without Arc, we wouldn't be able to safely share ownership of data between threads due to Rust's ownership and lifetime rules.

Wrapping shared data in Arc<Mutex<T>> is a common idiom in Rust for thread-safe shared mutable state. It ensures that the data lives as long as needed and that concurrent access is properly synchronized.

Mutex

1use std::sync::Mutex;

2

3fn main() {

4 let my_mutex = Mutex::new(5);

5 {

6 let mut mutex_changer = my_mutex.lock().unwrap();

7 *mutex_changer = 6;

8 } // mutex_changer goes out of scope - now it is gone. It is not locked anymore

9

10 println!("{:?}", my_mutex); // Now it says: Mutex { data: 6 }

11}In this example, we use a Mutex to provide synchronized access to a shared value. The lock() method is called to acquire a lock on the data, and it returns a MutexGuard, which allows us to safely modify the value.

The line let mut mutex_changer = my_mutex.lock().unwrap(); attempts to acquire the lock, and unwrap() is used to handle any potential errors during the locking process. Once we have the lock, we can mutate the underlying data using *mutex_changer = 6;.

Importantly, the lock is automatically released when the MutexGuard (in this case, mutex_changer) goes out of scope. This is a key feature of Rust's ownership model—it ensures that locks are properly released even in the presence of errors or early returns.

When we later print the Mutex, we can see that the data inside has been updated. This demonstrates how Mutex enables safe interior mutability in concurrent or single-threaded contexts.