Understanding memory model in C++

Table of Contents

What is Modification Order?

In multi-threaded applications, multiple threads often read from and write to the same memory location. Since thread execution is interleaved, the value observed by a particular thread depends on the exact sequence of operations. However, one key guarantee in C++'s memory model is that for any given variable, all threads agree on a single, well-defined order in which writes (modifications) occur. This order, known as the modification order, ensures that if one write happens before another, all threads will observe them in the same order, even if they execute at different times.

Similar to the modification order, we have thecoherence order. This is obtained by recording when each read operation was performed relative to the writes in the sequence. Just like the modification order, the coherence order of an atomic variable must be consistent across all threads. This is crucial for determining the possible values a read operation may return, as it ensures that a read always observes the value written by the preceding write in the coherence order.

In this article, we will cover three main memory models:Sequential Consistent, Acquire-Release, and Relaxed. The core principle underlying all these models, including the relaxed model, is that all threads must agree on the same coherence order for each atomic variable.

Types of Relationship Present

Sequenced-Before Relationship

Firstly, we have the sequenced-before relationship. This means that within the same thread, if evaluation A is sequenced before evaluation B, then evaluation A must complete before evaluation B starts in program order. This guarantees a well-defined execution sequence within a single thread.

Synchronizes-with Relationship

The synchronizes-with relationship occurs between atomic load and store operations. When a store operation in one thread writes to a variable and a load operation in another thread reads the same stored value, a synchronizes-with relationship is established. This guarantees visibility of the write to the reading thread. However, it is important to note that this relationship is not present in relaxed memory ordering and only applies to acquire-release and sequentially consistent models.

Happens-before Relationship

The happens-before relationship is established between A and B if: A is sequenced-before B, A synchronizes-with B, or if A happens-before X and X happens-before B (transitive property). Happens-before is important as it influences the coherence order in determining the relative order of read and write operations.

Types of Memory models

Sequential-Consistent

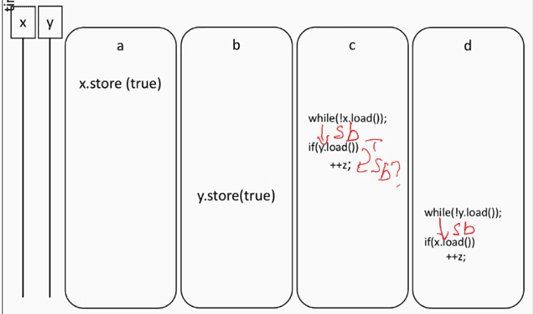

Sequential Consistency enforces that all threads must agree on the same order of operations. We've previously discussed that all threads must agree on a particular modification order for atomic variables, and that there must be an order to the writes. For sequential consistency, not only must there be an ordering for each atomic variable, but there must also be a global ordering for all variables. We will demonstrate the difference betweenacquire_releaseand sequential consistentwith an example below.

Thread 1:

1x.store(1, std::memory_order_release);Thread 2:

1y.store(1, std::memory_order_release);Thread 3:

1int a = x.load(std::memory_order_acquire); // x before y

2int b = y.load(std::memory_order_acquire);Thread 4:

1int c = y.load(std::memory_order_acquire); // y before x

2int d = x.load(std::memory_order_acquire);Suppose we have 4 threads: two threads writing to variables `x` and `y`, and two threads reading from those variables, but in opposite directions.

With acquire-release memory order, it is possible to observe thata == 1,b == 0 in thread 3, and c == 1 andd == 0 in thread 4. This happens because, although we enforce a modification order within each atomic variable, we do not enforce that the modification to `x` must be before or after the modification to `y`.

If the memory orderings are changed tostd::memory_order_seq_cst, then this enforces an ordering between the stores to x and y. Therefore, if thread 3 seesa == 1 andb == 0, it means the store to `x` must happen before the store to y. If thread 4 seesc == 1, meaning that the store to y has completed, then the store to x must have also completed. Thus, we must haved == 1.

If the memory orderings are changed tostd::memory_order_seq_cst, then this enforces an ordering between the stores to x and y. Therefore, if thread 3 seesa == 1 andb == 0, it means the store to `x` must happen before the store to y. If thread 4 seesc == 1, meaning that the store to y has completed, then the store to x must have also completed. Thus, we must haved == 1.

If a thread has observed a particular value, it can only observe values from that point onward in the program order. Similarly, if another thread wrote a value before this observation, then any thread that executes after must observe the updated value. This reflects the guarantee of sequential consistency, where operations appear to execute in a single, global order that is consistent with the program order of each individual thread.

Acquire-release

Acquire-release is similar to Sequential Consistency in that it allows for synchronizes-with and sequence-before. When an atomic store in thread A is tagged withmemory_order_release, and an atomic load in thread B is tagged withmemory_order_acquire, if thread B reads the value written by thread A, a happens-before relationship is established. This means that all memory writes that happened before the atomic store in thread A will also become visible to thread B. Essentially, whatever happens before the atomic store in thread A becomes visible to thread B, even if the operations are not atomic. This connection ensures synchronization across threads, particularly with respect to the modification order of different variables.

Relaxed

In relaxed ordering, there is no single global order of events. Different threads may observe the same operations in different orders — some threads might see them earlier, while others may see them later. Additionally, there is no synchronizes-with relationship, meaning that no happens-before relationship exists between threads. However, the modification order of a specific variable is still observed in a consistent manner by all threads.

Memory order examples

Thread 1:

1x.store(1, stdmo::relaxed); // (a)

2y.store(2, stdmo::release); // (b)Thread 2:

1x.store(3, stdmo::relaxed); // (p)

2z.store(4, stdmo::release); // (q)

3x.store(5, stdmo::relaxed); // (r)Thread 3:

1while (y.load(stdmo::acquire) != 2) { } // (t)

2cout << x.load(stdmo::relaxed); // (u)

3while (z.load(stdmo::acquire) != 4) { } // (v)

4cout << x.load(stdmo::relaxed); // (w)In this example, the first and second cout statements must print either 1, 3 or 5. They will never print 0.

In this setup with three threads, we establish two synchronizes-with relationships: a with t, and q with v.

For the first cout statement, we know that x.store(1) must have occurred before printing. However, since x.store(3) and x.store(5) could have been executed in any order, the first cout may print 1, 3 or 5

For the second cout statement, the synchronizes-with relationship between q and v guarantees that x.store(3)must have occurred (due to the transitive property of happens-before). Consequently, the second coutmust also print 1,3 or 5.

Atomics

Atomic operations provide safe, lock-free synchronization between threads without requiring explicit locks. Atomic operations do not directly flush data to or fetch data from DRAM. Instead, they rely on the CPU's cache coherence mechanism to guarantee correctness and visibility across cores.

Modern CPUs implement hardware cache coherence protocols such as MESI, MESIF, or MOESI. These protocols ensure that all cores observe a consistent view of shared memory by coordinating the state of cache lines across private CPU caches.

When a core modifies an atomic variable, the cache line containing that variable transitions into an exclusive or modified state in the writer's cache. At the same time, the coherence protocol invalidates that cache line in all other cores, preventing them from reading stale values from their local caches.

If another core later reads the same atomic variable, it will experience a cache miss due to the invalidated cache line. The core then performs a coherent read through the memory hierarchy and fetches the most recent value—often directly from another core’s cache rather than from main memory. This is why atomic reads remain fast despite strong synchronization guarantees.

On x86 architectures, atomic read-modify-write operations are commonly implemented using LOCKprefixed instructions. These instructions enforce exclusive ownership of the cache line and integrate directly with the coherence protocol, ensuring cross-core visibility without explicit cache flushes.

Atomic operations are indivisible at the hardware level. On many architectures, they compile down to a single atomic instruction (such asLOCK CMPXCHG), preventing interleaving race conditions when multiple threads access the same memory location.

Compare-and-Swap (CAS)

Compare-and-Swap (CAS) is a fundamental atomic read-modify-write primitive used extensively in lock-free data structures. Conceptually, a CAS operation reads a memory location, compares it against an expected value, and, if they match, atomically replaces it with a new value. The operation returns true when the swap succeeds and false when it fails.

In C++, this primitive is exposed via compare_exchange_weak and compare_exchange_strong.

compare_exchange_weak may fail spuriously, even when the expected value matches the atomic's current value. For this reason, it is typically used inside retry loops. When the operation fails, the expected parameter is automatically updated with the current value of the atomic variable.

compare_exchange_strong only fails when the expected value genuinely differs. It is best suited for cases where a single CAS attempt is performed and failure is handled explicitly.

1Node* old_front = m_queue_front.load(std::memory_order_acquire);

2

3while (true) {

4 Node* new_front = old_front->next.load(std::memory_order_acquire);

5

6 if (new_front == QUEUE_END)

7 return std::nullopt;

8

9 if (m_queue_front.compare_exchange_weak(

10 old_front,

11 new_front,

12 std::memory_order_acq_rel)) {

13 break;

14 }

15 // On failure, old_front is updated automatically

16}In this example, the current front pointer is first loaded using acquire semantics. The compare-and-swap then attempts to advance the queue head atomically. If another thread modifies the front concurrently, the CAS fails and updates old_frontwith the latest value, allowing the loop to retry safely.

This retry-based pattern is fundamental to lock-free queues with multiple producers and consumers. It avoids blocking, minimizes cache contention, and leverages hardware cache coherence to achieve efficient cross-core synchronization.

What is the ABA problem?

The ABA problem occurs in CAS-based lock-free code when a pointer's value changes from A to B and then back to A before a thread's CAS, causing the CAS to succeed on a different object at the same address.

For example, Thread 1 reads the head pointer into oldHead(address A). Thread 2 pops A, pushes B, frees A, allocates a new node at the same address A, then pushes it. Thread 1's CAS sees head == oldHead (A) and succeeds—wrongly operating on the new A.

Why the ABA Problem Only Affects Pointers:ABA arises from reusing memory addresses. Plain integers or other non-pointer values cannot be freed and reallocated at the same address, so they are not vulnerable.

Ways to Mitigate ABA:

• Version-Tagged Pointers: Wrap each pointer in a small struct that also holds a version counter. On every update, increment the counter before performing CAS on the combined pointer+version. Even if the pointer address returns to its old value, the version will differ and CAS will fail.

• Hazard Pointers: Give each thread a slot in a global hazard array where it publishes the pointer it is about to access. When removing (retiring) a node, defer its deletion and later scan the hazard array—only reclaim nodes not present in any slot. This ensures memory is never freed or reused while another thread might still hold a reference.

Acquire-Release Semantics for Read-Modify-Write Atomics

Acquire–Release semantics are most commonly used with read-modify-write (RMW) atomic operations such as fetch_add, fetch_sub, and compare_exchange. A single RMW performed with memory_order_acq_relacts as both an acquire and a release in one atomic step.

On the write side, the release semantics ensure that no earlier loads or stores can be reordered after the atomic operation. This guarantees that any data produced before the RMW remains visible to other threads that later observe the atomic update.

On the read side, the acquire semantics ensure that no subsequent loads or stores can be reordered before the atomic operation. As a result, the thread performing the RMW observes all data that was published by another thread that performed a corresponding release.

memory_order_acq_rel should be used when an atomic operation both consumes shared state and publishes new state for other threads. This commonly occurs in reference counting, where decrementing the count may trigger safe object destruction when it reaches zero.

Another common use case is lock-free data structures such as queues or stacks. A CAS operation that reads an old pointer value and publishes a new pointer must enforce ordering in both directions to ensure correctness across threads.

Acquire–release RMW operations also appear in combined publish–subscribe patterns, where a single counter or flag update both consumes existing state and signals the availability of new state for other threads to observe.